In his debut article for The Football Front, Nick Meredith tackles the rise of the contemporary 'Nine and a Half' position.

In his debut article for The Football Front, Nick Meredith tackles the rise of the contemporary 'Nine and a Half' position.Wayne Rooney is on a hot streak. His goal against Chelsea brought his domestic tally for this season to 10 goals in 6 starts. Relishing his deeper-lying role in United’s fluid 4-4-2/4-2-3-1 cross, he is both creator in chief and predatory goalscorer for his high-flying side.

It wasn’t always this way, though. In the 2010/11 season he suffered an early dip of form before roaring back as United’s focal point. Alongside the lethal Javier Hernandez, Rooney bagged 11 goals and as many assists. In the season before that, (the 2009/10 season), things were again slightly different: instead of being his side’s main creative outlet, he was their main goalscorer, scoring 26 goals as United were pipped to the title.

So the eternal question springs up, as it often does. What IS Rooney? For people trying to slot him into a specific role, it's a nightmare. Is he a classic ‘Number 10?', creating chances for others and roaming deep into midfield? The 2010/11 season would seem to suggest so. But what about another wonderful season he had, in the 2009/10 season? This was arguably his best season, Rooney was often deployed as a lone striker and was the main goalscorer of the team. So is he a ‘Number 9?’, a powerful focal point for the attack and the side’s main goal threat? This season would seem to suggest, he is somewhere in between.

The ‘nine and a half’

This season, Rooney has been deployed in the withdrawn position he made his own last season, but he has added the goalscoring prowess of the 2009/10 season. Rooney has been drifting around behind a striker such as Danny Welbeck or Hernandez, he has found space in which to both create and score. He is equally a goalscorer and a creator. The usual roles don’t apply here. He is far too complete to be classed as either a ‘9’ or ‘10’. In fact, he slots into a much rarer role: the ‘nine and a half’.

The idea of a ‘nine and a half’ isn’t new – Marco Van Basten was arguably its greatest exponent – but very few have the talent to carry it off. Finding a player complete enough that he can both create and score is hard enough, and finding one who is good enough to fulfil the role to its full extent is rarer still. The role is becoming more and more prevalent nowadays. However, due to the increasing completeness of footballers. Decades ago, a footballer could excel at one thing and make it into a team. Since then, the successes of Rinus Michel’s ‘Total Football’, Arrigo Sacchi’s ‘Gli Immortali’ and now the current Barcelona sides, in which universality was and is still the key, it has shaped footballers into much more rounded athletes. Even a decade ago, strikers like Robbie Fowler – who is short, not creative, not strong and not quick – could thrive in the Premier League because of his wonderful finishing. Perhaps, now he wouldn’t even get a look in.

Players like Lionel Messi, Wayne Rooney, Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Diego Forlan are all complete strikers and are excellent ‘nine and a half’s', on top of being truly world-class strikers. There are many 'nine and a half's' players in the modern game. In the Premier League alone, there are at least five – Rooney, Robin Van Persie, Sergio Aguero, Carlos Tevez and Luis Suarez. All five combine the twin talents of creativity and goalscoring. All of them are wonderful strikers, and are the Premier League’s best, which brings us onto the meat of this article.

The rise of the complete forward

Why are ‘nine and a half’s so effective? The simple answer could be their versatility, which of course, always make them an asset – for instance, Aguero has been used both playing off a main striker and as the main striker himself this season – but that is more to do with their worth to the team rather than their effectiveness on the pitch. In essence, the 9 ½‘s effectiveness is based around uncertainty. You have a variety of options to stop a forward, but realistically, you can only implement one. When faced with a striker who can do so much so well, how can you possibly defend against him?

Let’s compare Rooney to another top striker, say the ex-Inter poacher Samuel Eto’o. Both of them are wonderful players, but Eto’o, whilst a truly lethal finisher and one of the best strikers of the past decade, is clearly by no means a 9½. Creatively, he doesn’t have the vision and passing ability to be able to split the defence with an incisive through-ball or create a chance for another in such a way that real 9 ½s like Rooney or Messi can. What he does have is the aforementioned eye for goal, terrific movement and blistering pace. When faced with a pacey, clinical striker, the main worry for the defence is balls over the top and in behind the defence for him to chase, beating the defender with his pace in order to get in a one-on-one with the keeper. However, the easiest solution is for the defense to sit deep and allow the opposition to play in front of them, thus denying the striker space in behind for the rest of the team to roll balls through.

Try this with Rooney, though, and a whole new problem is opened up. A 9 ½ is equally happy to drop deep as he is up against a central defender, he can drop off and exploit the extra space that has opened up as a result. Whilst an opposition defence wouldn’t mind Eto’o doing this due to his creative skills being rather poor by comparison to the likes of Messi or Rooney, but allowing Rooney to do it would be suicide. With space and time on the ball and willing runners from midfield, Rooney can destroy any defence with ease.

So how DO you stop them?

Man-marking a dangerous player is a trick as old as football itself. Having a deep holding midfielder with strict man-marking instructions is all well and good, but unfortunately the 9 ½ is usually equal to it. If we take our case example of Rooney, he often drops even deeper thus, escaping the attentions of the deep midfielder or even leaving a gaping hole in front of the defence for others to exploit as the marker follows him (Fig. 1) . It could also lead to Rooney pushing up higher, forcing the midfielder to drop into the defence and leave a shortfall of numbers in midfield (Fig. 2).

Transparent positions show how each player started in the movement. Click to enlarge.

One final method could just be ignoring the 'nine and a half's' completely, and treating them like any other player. It goes without saying that this is an extremely risky gambit considering how most 9 ½s are such influential and talented players. Andre Villas-Boas arguably attempted this when his Chelsea side played against Manchester United, and achieved a partial success in that Rooney was relatively quiet compared to recent games. On the other hand, Rooney scored one goal, he hit the post, took five shots and won two dribbles. These stats are hardly calming, especially as its the opposition’s best striker.

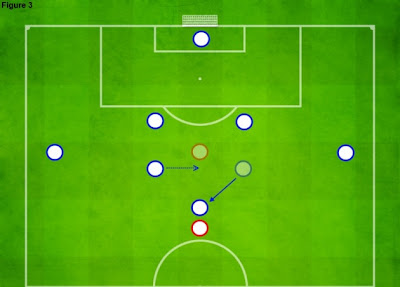

So with most traditional methods useless, what could a manager use to stop a 9 ½? There are two possible solutions, one rather practical and another highly experimental. The first is to just set up with two deep holders, a 4-2-3-1 for instance. Uruguay did a variant of this in the World Cup, with their two destroyers, Diego Perez and Egidio Arevalo, solidly staying in front of their defence. If a 9 ½ ever tried dropping deep to find space, such as Holland’s Robin Van Persie did in their semi-final match, one of the two would track him. Van Persie was free to move as deep as he wanted, the other holding player remained in position sweeping in front of the defence (Fig. 3). In this case, this was complicated by the presence of Wesley Sneijder playing as a trequartista, though Uruguay got around that by fielding another solid central midfielder, Walter Gargano, ahead of the midfield pivot. Gargano was comfortable dropping in and helping out with the defensive legwork. Although Uruguay lost the game, it would be hard to blame the midfield holders for doing their job, or indeed to praise a relatively ineffective Van Persie. But the knock-on effect of this, of course, is that unless the midfield destroyers are very talented the team loses it's passing ability from the centre of the pitch, effecting fluidity as a result.

The second method involves using a zonal marking system in order to keep the 9 ½ tracked across the pitch without compromising shape. Instead of using a strict man-marker, when a 9 ½ tries moving deep or out of the man-marker’s comfortable range, he passes him onto a more advanced midfielder higher up the pitch. In theory, this would work perfectly. In practice, the move is extremely difficult to pull off, requiring exceptional teamwork and awareness on the pitch by the defenders.

How the 9 ½ role will develop remains to be seen, but as footballers get more and more well rounded, new ways of stopping 9 ½s will be developed. I mentioned at the start of this article that strikers are becoming less one-dimensional, but the same is also true of defenders. Nowadays cultured defenders like Gerard Pique, David Luiz and Thomas Vermaelen are becoming much more prevalent. With their ability to step out of defence and into midfield, they can track the deeper movements of strikers with more ease than ever before. This will only aid them in the constant tactical battle between defenders and strikers. As it is, finding cultured defenders is hard, and the ‘nine and a half’ continues to be one of the most potent weapons a manager can bring to bear on the field.

![Validate my Atom 1.0 feed [Valid Atom 1.0]](valid-atom.png) // technoaryi

// technoaryi

No comments:

Post a Comment